HISTORICAL SKETCHES

of the Bench and Bar of Lycoming County, Pennsylvania

[Contents] [Last-Part 2] [Next-Part 4]

“For they are two things,

wisdom and law together;

and therefore it is said: nobody

is a judge through learning;

although a person may always learn,

he will not be a judge unless there be

wisdom in his heart; however wise

a person may be, he will not be a

judge unless there be learning with the wisdom.”

—Ancient Laws and Institutes of Wales

Book VIII, Chap. XI, p. 493, Howell the Good.

The name Lewis first appears as a family name in Dolgelly, Merionethshire, Wales. Prince Cadwiggan, fifth in descent from King Howell, the famous law-giver of Wales, was himself Lord Nannau, and tenth in descent from him followed another Howell, Lord Nannau, one of whose grandsons, John, made him self a home in this parish of Dolgelly. He gave his son a name destined to become a family name, both in the homeland and in the colonies. Two generations passed before Lewis — for such was the name — was to have a descendant by the name of Lewis. This Lewis ap Robert, i.e., son of Robert, had a sister, Margaret, who became the wife of Rowland ap Ellis, or as he was known in later life, Rowland Ellis. So it was that Lewis ap Robert became known, not only as Lewis Robert, but Lewis Owen and Owen Lewis as well.

The name Lewis first appears as a family name in Dolgelly, Merionethshire, Wales. Prince Cadwiggan, fifth in descent from King Howell, the famous law-giver of Wales, was himself Lord Nannau, and tenth in descent from him followed another Howell, Lord Nannau, one of whose grandsons, John, made him self a home in this parish of Dolgelly. He gave his son a name destined to become a family name, both in the homeland and in the colonies. Two generations passed before Lewis — for such was the name — was to have a descendant by the name of Lewis. This Lewis ap Robert, i.e., son of Robert, had a sister, Margaret, who became the wife of Rowland ap Ellis, or as he was known in later life, Rowland Ellis. So it was that Lewis ap Robert became known, not only as Lewis Robert, but Lewis Owen and Owen Lewis as well.

It was a son of this Lewis, born about 1680, who was given the name of Ellis Lewis, who finally determined the family name. This family were Quakers, and because of the persecution of that faith under Charles II, James II and William and Mary, determined to join the prosperous Quaker colony on the banks of the Delaware. About 1698, Ellis Lewis, his mother, and Owen Robert were persuaded to make the journey, when sudden illness delayed their departure temporarily. This delay proved to be more serious, than intended, for they were caught up in the movement under William and Mary’s government to displace the Irish Catholics with Protestant settlers from Britain, and were carried past Dublin southward through Kildare into northern Queens County in the neighborhood of Mount Melick.

Whether the next ten years were all spent there is not known, but the continual strife must have had little inducement for the peaceful Friends to further delay removal to the colony of Pennsylvania which Rowland Ellis found so attractive. Certain it is that Ellis Lewis and his mother’s family did undertake the long voyage to America in 1708, for the Mount Melick meeting gave Ellis a certificate the 25th day of the 5th month of that year. He was at this time unmarried and about twenty-eight years old.

Lewis did not purpose living in Philadelphia, but in Haverford where Uncle Rowland Ellis lived. He was married at Concord meeting in 1713, and finally settled at Kennett where a third son, Ellis Lewis, Jr., was born March 22, 1719. As a young man he heard about how some venturesome settlers had crossed the Susquehanna into Indian lands, causing much trouble. Young Lewis joined a company on horse-back. They finally reached the virgin valley just below John Harris’ trading post and ferry, now Harrisburg, and settled in the Red Lands Valley. But that too, soon became crowded with more than its share of westward moving settlers. Then in 1749, he joined other settlers in the region between the South Mountain and the river at a place which was to be called York. He had married in 1744, Ruth Wilson, at the old Birmingham meeting, and they had a son, Eli, born January 31, 1756. Then came the time of difficult choice for a Quaker, when the Associators began to organize, whether he wanted “worldly liberty”, or remain a Quaker. There is no record of his activities in 1775-6, but he must have had at least a modest part in military preparations, for in 1777, he was commissioned Major in the First Battalion of York County, and is said to have taken part in the battles of Brandywine and Germantown, becoming a British prisoner. Apparently he was not read out of the meeting because of his military activities, because he was married September 11, 1778, to Pamela Webster, in the Newgarden meeting.

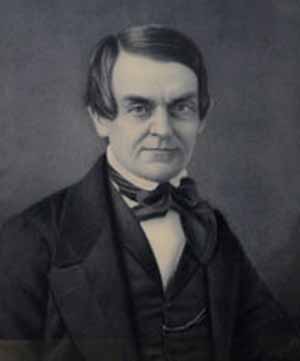

Major Eli Lewis was a devoted Federalist and rallied his friends in support of the new constitution, in 1787. He had written articles for The Pennsylvania Chronicle and York Weekly Advertiser. About 1789, the York Chronicle’s plant was moved to the ambitious town of Harrisburg, and Major Lewis within a year became the proprietor of Harrisburg’s first newspaper. Major Lewis returned in due time to the Red Lands Valley and his old home, the birthplace of his children. Here he laid out a village and christened it Lewisberry. And here on May 16, 1798, his son Ellis was born. But the latter soon lost his parents and was left an orphan at the age of nine.

John Wyeth, who had bought his father’s newspaper in 1792, advertised for an apprentice. As 1808 and 1809 passed on, his guardian heard of the success of Joseph Findley’s Academy at Harrisburg. It was no small opportunity for a youth to be in Wyeth’s printing office, for in those days, the newspaper office was the book-store and general literary clearing-house for the entire region. So Wyeth agreed to teach “the art and mystery of a Printer,” for seven years, and the boy was not to absent himself from his master’s service without leave. But he grew restless and determined to break his bonds, and soon left Harrisburg and the office. Mr. Wyeth was in no mood to lose two years of his apprentice’s services and advertised for him, offering a reward of twenty dollars for his return.

For more than eight months nothing was heard from him. That he would leave the state and go where his skill as a printer could be exercised was not to be doubted. Assuming the name of Henry Van Ellenburg, he soon found work in New York. He was variously employed in New York, Frederick City, and Westminster, Maryland. He now planned to open his own news paper at Westminster, when he heard that a Mr. Simpson who owned the Advertiser in Williamsport was seeking a partner. In 1818, even before Lewis arrived, Simpson announced to his patrons that his editorial duties had ceased and Lewis’ begun. This premature announcement disgusted Lewis, and so he went over to the Gazette, owned by L. K. Torbert instead. It was not long before Mr. Torbert’s ill health caused him to sell out to Lewis. Lewis had later to defend himself against Simpson from assault for refusing to print an article dealing in personalities.

His standing in the community was due to his championing the cause of “the plain, blunt men,” the common people, often in opposition to the influential element generally known as the “Hepburn connection.” He was interested in taking part in public affairs especially on behalf of Governor William Findley, who had been in public office since 1817, and was up for re-election again against a rival Democrat, Col. Joseph Heister, of Berks County. Fleister was successful and Lewis then abandoned his purpose to enter public life. But he remained a great favorite in Williamsport, and a person to be reckoned with in democratic politics. One event which extended his influence was his marriage to Miss Josephine Wallis, the daughter of Joseph Jacob Wallis, on November 21, 1822.

He had disposed of his newspaper, in July 1821, to his friend, Tunison Coryell. About the middle of 1820, he had begun to study law in the office of Espy Van Horn, then Deputy Attorney General for Lycoming County. On September 3, 1822, he was admitted to the bar.

A dark horse appeared in the person of John Andrew Shulze, in 1823, to whose cause Ellis Lewis now attached him self. Through these efforts, he was appointed Deputy Attorney General, upon recommendation of Judge Seth Chapman and his associates of Lycoming county, as well as Judge Herrick and his associates of Tioga County, by the new Governor.

As he was Deputy Attorney General for both Lycoming and Tioga counties, it was thought best for him to live at least part of the time in Wellsboro. However, his bright prospects were suddenly threatened by a disease in one of the lower bones of the leg. He was taken to Harrisburg in November 1827, and a delicate operation was performed on his tibia which was highly successful. He was also instrumental in that same year, in securing the establishment of the United States Court in Williamsport.

Bradford County was growing vigorously at that time and Lewis became interested in the newspaper plant there, so he decided to move to Towanda, as he had been admitted there May 1, 1829. (David Wilmot was admitted about five years later, and in a sense became Lewis’ successor at the Towanda Bar.) It was from Bradford County then that Ellis Lewis was elected to the House of Representatives and took his seat in December 1832. This independent representative solidly supported Governor Wolf.

The chief feature of the legislative session was the election of a U. S. Senator. Representative Lewis had vigorously attacked a resolution which purposed an inquiry into the mode of counting the votes for Governor at the last election. Governor Wolf was near enough to hear Mr. Lewis’ speech, and at once enlisted him as a leading adviser and supporter. On January 31, 1833, the Governor appointed Ellis Lewis as his Attorney General. He did not give up his seat in the House although that question was raised very quickly. The Northern Banner, the new name for the Old Settler, came to his defense with the argument that the Constitution expressly excepted the public office of Attorney at Law from the offices prohibited to a member of the Legislature. Apparently the Banner’s theory prevailed, as no more was heard about the matter.

His character and popularity may be shown by a few incidents. He appointed John Wyeth, Jr., son of the “old master” of his printing days as Deputy Attorney General. He afterwards told Associate Judge Charles D. Eldred that he did this to show that he nursed no resentment toward the family. In fact all his appointments were good, both in law and politics.

Another innocent looking incident came up in the Senate, on March. 12, 1833, that proved to be very significant. Some petitions had. come up from Lycoming County complaining that their venerable President Judge Seth Chapman had long passed the age of usefulness and that his continuance in that office was an obstacle to the ends of Justice. The Senate, as related above, had referred the matter to a committee, and his resignation had been accepted by Governor Wolf effective October 10, 1833. Here then was a vacancy in the President Judgeship in the old eighth district. This was the district in which Ellis Lewis had first won a place in public and private life as a printer, lawyer and publicist; where he had won his wife, and built his first home; where he was admitted to the bar; and where he had greater prestige than anywhere else in the world.

General McKean wished Lewis to retire from politics, for he felt Lewis’ ambitions and talents threatened his own aspirations toward the U. S. Senate. General Anthony was then in Congress and expected re-election, and would support the Attorney General, and of course, Lewis’ friend, William F. Packer, then Superintendent of the West Branch Division of the Pennsylvania Canal, as well as proprietor of the Lycoming Gazette, was indebted to McKean and Lewis alike. Ellis Lewis was therefore formally announced and pressed for the appointment to succeed Judge Chapman as early as July 31, 1833, by the Lycoming Gazette.

Joseph Biles Anthony and Dr. James Taylor were Lewis’ delegates from Williamsport to a Democratic County Convention and John H. Cowden and Joseph Williams were anti-Lewis. The McKean and Lewis interests became more and more welded together by the campaign, and on October 14th, his appointment as President Judge of the old Eighth District was drawn, and George M. Dallas, of Philadelphia, became the new Attorney General.

Lewis was but 35 years old when he succeeded Judge Chapman. Even in his short life thus far, the number of judicial districts had grown from five, and by the time he was admitted to the bar, had trebled in number, when the Fifteenth was erected out of the old Seventh (1806). Bradford and Tioga were gone, and by 1834, the old Eighth still contained Northumberland and Lycoming, with Columbia and Union as their companions.

Judge Lewis held his first court at Sunbury, and at once infused new life into the proceedings in all four counties. It is beyond the scope of this work to go into the local details of these four courts. However, several cases were tried in Williamsport which were of more than ordinary interest.

The first of these cases was fully reported by William F. Packer and A. Cummings, Jr.25 at the February Sessions 1836. The first murder trial in Lycoming County in which there was a conviction was that of John Price for the murder of an Irish man named Miller, near Muncy Dam, about February 1830. The murderer was convicted and imprisoned for a short time. (However, Meginness, in his Book of Murders, says he was found not guilty.)

The second murder, likewise connected with Muncy Dam, occurred October 14, 1835, when John Earls killed his wife, Catherine, by administration of arsenic in a cup of chocolate. He was the first person hanged in Lycoming County. His faithful (common law) wife lay on her bed of confinement. She died in great agony, and as Earls had been in the habit of abusing his wife, coupled with the fact that a short time before her death, Earls had bought a quantity of white arsenic at the apothecary shop of Bruner and Dawson in Muncy, he was at once suspected. Muncy Dam at that period was a hotbed of lawlessness; counterfeiting and horse-stealing being two of the outstanding accomplishments of this group of rivermen and fishermen.

Another circumstance which pointed the finger at Earls was his well known infatuation with a certain young woman named Maria Moritz. Out of this affair nearly all of Earls’ domestic troubles arose. He frequently told his wife if she could hug and kiss like Maria Moritz he would love her a great deal better.

Earls was represented by Anson V. Parsons, William Cox Ellis, of Muncy, and Robert Fleming, while Deputy Attorney General James Armstrong and Francis C. Campbell conducted the prosecution. The trial began February 2nd and the verdict of the jury was handed in on February 15th.

At the February sessions 1836, John Earls was arraigned for trial before President Judge Lewis, and his two associates, John Cummings and Dr. Asher Davidson. A true bill having been found by the Grand Jury at the November Sessions, 1835, a continuance was granted due to an injury to one of the witnesses.

There were 57 witnesses called in the case. Three of Earls’ seven children, Mary Ann, aged 15; Susannah, aged 14; and Samuel, aged 11, were called. These witnesses testified that Earls had mistreated his wife on more than one occasion; that he had dragged her out of the house by the hair; and locked her in the cellar in cold weather. On another occasion, he had shoved her into the watering trough of Solomon Mangus. There was testimony that he had bought “ratsbane” or white arsenic on the day of the last general election. There was also considerable testimony, on the part of the commonwealth, as to Earls being frequently seen with Maria Moritz under compromising circumstances.

The addresses of counsel for both sides were able and very exhaustive. But the medical profession also shone, and exhibited great learning. Dr. Hepburn, Dr. Dougal, of Milton, Dr. Kittoe and Dr. Ludwig were all of great assistance to the court. But the outstanding person in the entire case was of course Judge Ellis Lewis. He himself displayed a profound knowledge, which led Beck to say, in the 1851 edition of his Medical Jurisprudence (Vol. 11, p. 546) : “I know of no case to which I would sooner refer than this as a proof of the advanced state of Medical Jurisprudence in this country.”

The case was appealed to the Supreme Court, (1 Wharton 525) which in April denied the appeal, and then on May 21st, a few days before he was to be executed, Earls made a full and complete confession, which Packer and Cummings also printed in full for the benefit of his orphan children. This confession is most revealing, and after having read my account of the trial26 Dr. Elsie Murray, an eminent psychologist of Cornell University, wrote that the account of the Earls trial was a marvelous study in psychology, that is, the slowly accumulating exasperations and unsatisfied longings in Earls’ tortured brain which culminated in the murder. John Person, Sr., also made the same observation.

Judge Lewis, in pronouncing sentence, said in part:

“Of all crimes, that of wilful and deliberate murder is perhaps the most foul and unnatural. Of all means by which a deed so dire can be committed, that of poison evinces, perhaps, the most cold-blooded deliberation. Of all persons who may be subject to this crime, the wife of your bosom — the mother of your children — the partner of your lot — whose name and whose civil existence was merged into your own, should have been the last to be thus destroyed in the hour of unsuspecting confidence. Of all occasions for a deed so dreadful, the selection of that period when she was prostrated upon her bed of confinement, with the newborn babe in helpless infancy at her side, manifests ‘a heart the most regardless of social duty and fatally bent on mischief’. Of such a murder, and with such attending circumstances, a jury of your country have pronounced you GUILTY.”

Judging from Far Away

An amusing but significant incident, showing how widespread Judge Lewis’ reputation as a judge had become even at this time, occurred about two years after the Earls case had been tried. Early in 1838, shortly before the Iowa Territory had been carved out of Wisconsin on June 12th following, at a time when the courts had not yet begun to function, two men were caught and charged with passing counterfeit money. Dubuque was then but a frontier settlement only five years old, established the very year Judge Lewis became a judge in “the far east.” Since no court was in operation at the time, a sort of Lynch Court was constituted. It resembled a town meeting, and a gentleman by the name of Peter Hill Engle presided. Apparently he got along very well, for the men were fairly tried and convicted. The testimony against the one was perfectly clear; he had passed a number of spurious notes, and had a large amount in his possession. He was sentenced to receive a certain number of lashes, as there were no jails. The other had passed no bad notes, nor were any found in his pos session; but on the contrary, all the money found in his possession, amounting to eight hundred dollars, was genuine. The evidence against the two was that they had lodged at the same inn the previous night and had been together that day. The primitive jury drew the inference, from the circumstances, that one had passed the notes, and the other was the treasurer, to take charge of the genuine money received in the business operations. The one found guilty of being the treasurer immediately appealed from the decision. On his being asked to what tribunal he appealed, he thought a moment, and then answered: “I appeal to Judge Lewis, of Pennsylvania.”

The case was accordingly certified to Judge Lewis by President Engle, together with his written opinion, citing the reasons of the court for its decision. The defendant, Titus Losey, had been sentenced to pay a fine of eight hundred dollars, and the record showed that the fine had been collected. It seems somewhat odd that the amount of his fine was exactly the amount he had had in his possession.

Judge Lewis entertained jurisdiction, and gave a written opinion that the mere circumstances of being found in company with a counterfeiter was not sufficient of itself to rebut the general presumption of innocence; that man was naturally a social animal; that this feeling would be more readily manifested when two strangers meet in a new country, and lodge at the same inn, and are journeying in the same direction. On the whole of the evidence, the judgment was reversed, and restitution of the fine awarded. The record was then transmitted to Judge Engle, and the decision was promptly obeyed and the money refunded.27

Probably the most notable of the cases which came before Judge Lewis in the Eighth District was one of both national and international interest, which was tried near the close of his decade there. In August 1842, the case of Hall v. Armstrong came be fore Judge Lewis, at Williamsport. The plaintiff was a Baptist minister by the name of Hall, and he asked protection against the threats of a man named Armstrong, because the latter’s daughter, a minor, who had been baptized in her mother’s faith (Presbyterian) had been re-baptized by immersion by Hall against the father’s absolute prohibition. The court placed the father under bond to keep the peace, but found Hall’s act unlawful. After discussing the nature of parental authority, and quoting various authorities, he explained the common law on the subject and continued:

“The highest tribunal in the commonwealth dare not attempt to estrange the child from the religious faith of its parents. Shall this power be exercised by a private individual because he happens to be a minister of the gospel! Shall any man, high or low, be allowed to invade the domestic sanctuary — to disregard parental authority established by God Almighty, to set at naught the religious obligations incurred on behalf of the child at its baptism — to seduce it away from its filial obedience or even to participate in its disregard of parental authority, for the purpose of estranging it from the faith of its parents, or introducing it into a religious denomination different from that to which its parents belong? God forbid that the noblest and holiest feelings of the human heart should be thus disturbed — that the harmony of the domestic circle violated that the endearing relations of parent and child should be thus broken up and that the family altar itself should be thus ruthlessly rent in twain and trodden in the dust.

“One of the members of this court is a minister of the gospel of the Methodist persuasion, and he makes no claim in behalf of that denomination to the exercise of any such authority. Another of the judges is attached to the Episcopal church28, and he repudiates every pretense of such a claim on behalf of that church the remaining judge belongs to no particular religion, and he denies to all alike the exercise of any such power. No member of this court belongs to either of the religious societies whose rights are brought into conflict in this investigation. This decision must therefore be free from denominational influences. . . . Without the slightest disrespect for the Baptists . . . it may safely be affirmed that the morals of the child were not endangered by remaining within the folds of the Presbyterian church.

“We wish it to be distinctly understood that no imputations are cast upon the motives of Rev. Mr. Hall. We believe he acted conscientiously as he conceived to be right. But, in our opinion he has transcended the divine and human law in disregarding the authority of the father over his offspring while in his minority. This is the opinion of the constitutional authority — the result of our conscientious convictions of the law, and it is hoped that he will feel bound to respect it accordingly in any after proceedings. In refusing to render unto Caesar the things that are Caesar’s, he has fallen under the condemnation of the law. It is therefore ordered that he pay the costs of this application.”

This opinion was republished almost universally throughout this country, with the cordial approbation of every religious denomination, except a few of those who belonged to that of the offending preacher. The Roman Catholics themselves were among those loudest in their approval. The editor of the United States Gazette, himself a Roman Catholic, agreed with Judge Lewis’ decision. Another eminent Roman Catholic wrote a work including this decision, which formed a part of the Pope’s library, to which book the Pope himself referred his American priests.

Chancellor Kent made a note of it in his revised edition of his Commentaries. Judge Robert C. Grier, later a U.S. Supreme Court Justice, wrote Judge Lewis that the conclusion was incontrovertible. All in all it must have come as quite a surprise to the Rev. Mr. Hall to have been involved in such an important controversy.

The IV Abolition Riot Case

At this same term of court, the Muncy Abolition Rioters were also tried. Enos Hawley (father of Robert Hawley, later a member of our bar and Prothonotary, 1850), may be said to have been a pioneer abolitionist. He and other Quakers engaged the services of a lecturer (Whose name has not come down to us) to lecture on the subject, and the latter stayed at the Hawley home in Muncy. About eighteen of the most prominent young bloods of Muncy broke up the peaceable meeting in the school house, threw rotten eggs at Mr. Hawley and the lecturer, afterwards making a violent assault on Hawley’s home.

The Grand Jury found a true bill and the case proceeded. On Saturday evening, Abraham Updegraff, also a Quaker, who conducted a general store with Jacob Grafius located across the street from the Court House, went over to look in at the Court. Scarcely had he crossed the threshold, when he heard his name called a talesman, the panel having been exhausted. He soon found that the real plaintiff was his old friend, Enos Hawley. Judge Anthony was presiding but having been counsel for some of the defendants, declined to sit, and called upon Judge Lewis then sitting at Lancaster, to preside in his stead.

James Armstrong represented the defendants, and Francis C. Campbell was Mr. Hawley’s attorney. Mr. Updegraff says the defendants had two lawyers who made long, frothy speeches, claiming that all abolitionists were dangerous, stirring up dissension, and but for them the slaves would be eminently happy, never dreaming of liberty. Campbell thought the evidence so clear that he deemed it unnecessary to make a long exhaustive speech. The court gave a very fair charge to the jury, and stated that he would wait for their verdict until twelve o’clock midnight or otherwise they were not to separate until Monday.

On reaching the jury room, the foreman at once proposed a ballot, which resulted in eleven for acquittal, and one for conviction. The foreman at once commenced to argue to the unknown Juror, berating all abolitionists, and another juror said he had never seen one. Abraham Updegraff then arose to his full height, and said: “Take a look”. He soon found that three of the jurors were honest Dutchmen, who scarcely understood the English language. Updegraff talked to them in their native tongue, and they “soon came around alright.” On the second ballot, there were three for acquittal. Davy Dykins then rapped on the door, and said it was fifteen minutes before midnight. They then took an other ballot and were solid for conviction. Judge Anthony then arose and asked that sentence be suspended until Monday morning, which was granted. That night, A. D. Wilson, William Cox Ellis, John W. Maynard and others hastened to the capital and convinced the Governor of the urgent necessity of granting a pardon for the Muncy bloods, and this before the defendants had even been sentenced. So when the court opened on Monday morning, there was the pardon on hand for all defendants, granted by “Previous Pardon Porter” as Abraham Updegraff dubbed him.

President Judge at Lancaster

Judge Lewis’ career now broadens out and he next became President Judge of Second (Lancaster) District January 5, 1843. During his judicial career in Lancaster his opinions were published. It was during the last year of his stay in Williamsport that Messrs. Wallace and David, at Philadelphia, began to publish the Pennsylvania Law Journal. In this Judge Lewis’ decision in Hall v. Armstrong appeared, along with Chancellor Kent’s letter regarding it.

In 1845, a well known law publisher in Harrisburg sought his services as an editor of a “New Library of Law and Equity”, the board of editors including Francis J. Troubat, of Philadelphia; Hon. Ellis Lewis, and Wilson McCandless, of Pittsburgh. This continued through most of his career in the Second District.

To be so learned a judge in a college town was almost un heard of, except as a Professor of Law. Franklin College, dating back almost to the Revolution, had been combined with Marshall College, formerly at Mercersburg, about six years before. Then in the summer of 1846, a chair of Law and Medical Jurisprudence was established for which they evidently had Judge Lewis in mind. He apparently did fill that chair for a while, although Dr. J. H. Dubbs, the college historian, finds no record of the further progress of this professorship.

Lewis next undertook a revision of Kent’s Commentaries, which appeared about the time the Chancellor lay dying. Lewis’ learning was recognized by Transylvania Univ., Lexington, Ky., and Jefferson College, Canonsburg, Pa., LL.D. 1848; Philadelphia College of Medicine, Hon. M.D.

Supreme Court Justice

In 1850, popular demand for an elective Judiciary came to a climax. The amendment was carried by an overwhelming vote. Candidates for the Supreme Bench were brought forth during the winter, and it soon became plain that Judge Lewis was in the foreground. Following the election, the casting of lots resulted as follows: a three year term and the Chief Justiceship for Black; a six year term and succession to the Chief Justiceship for Lewis; the nine year term to ex-Chief Justice Gibson; the twelve year term to Lowrie and the fifteen year term to Coulter.

Judge Lewis’ first opinion as a member of this court was on a construction of Stephen Girard’s will (5 Harris 111). An other case involving corporations showed his editorial experience in bringing a difficult subject within the range of popular comprehension (5 Harris 141).

When the court sat at Philadelphia in 1852, Lewis delivered fifteen of the sixty-two opinions and dissented but once. In one of these opinions (Heckerman v. Hummel, 7 Harris 69) is found the following:

“Fortunately for the consistent and humane administration of justice, the courts of this country are no longer influenced by the feudal policy which favored the eldest son to the exclusion of other claims; and are not restrained, as Lord Eldon was, from contradicting a decision of the House of Lords. . . . After a lapse of three score years and ten the memory fails, the witnesses die, and documents are lost or mislaid. It is therefore difficult, and frequently impossible, to establish, by positive evidence, the facts of an ancient transaction. The law, in furtherance of justice, and for the protection of society, has, in such cases, substituted for positive evidence the doctrine of presumptions. A possession of twenty-one years is not only sufficient defense to an ejectment, but is a title on which the plain tiff may support such action against another. Deeds thirty years old, in accordance with the possession, may be given without proof. Thus, as ‘the scythe of time destroys the evidence of title, the hour-glass measures out the period when those evidences are no longer necessary.’”

I can well recall dear old Sammy Williston telling a startled first year student in his class on Contracts, “Mr. ________, if you think the House of Lords is wrong, do not hesitate to say so.”

Chief Justice Lewis

In due time, Lewis succeeded Black as Chief justice and his increased prominence as Chief Justice brought additional honors. He received honorary degrees of LL. D. and M.D., and some one suggested that if his honors had been equal to his deserts, D.D. might also have been appropriately conferred upon him. He ever bore in mind the doctrine of Socrates: “Three things belong to a judge; to hear courteously, consider soberly, and give judgment without partiality.” This specifically applies to Judges, but I think the words of Micah have a broader application to all lawyers as well as judges: “What does the Lord require of thee, but to love mercy, do justice and walk humbly before thy God ?“ (Micah 6:8).

During this period, the Supreme Court, in addition to sitting in Philadelphia, also sat at Sunbury, Harrisburg and Pittsburgh. During the spring of 1857, several changes occurred in the personnel of the court. Justice Black, who still had a long term to serve, was commissioned by President James Buchanan as his Attorney-General, and his place was filled by the appointment of James Armstrong, on April 6th, who served only until the November election.

Two days before the inauguration of Buchanan, and four days before the Dred Scott decision, the Democratic State Convention nominated William F. Packer for Governor, and Lewis for another term. But Lewis declined stating that he had already served twenty-four years, a longer period than any other living Judge in Pennsylvania, and that he desired to return to private life. He had become old beyond his years, and had begun to show it. But he was never an idle man. He was President of the Williamsport and Elmira Railroad, and also helped organize the Sunbury and Erie Railroad, the Camden and Atlantic Railroad, and many other important enterprises.

In 1858, he was appointed one of the commissioners to revise the Criminal Code of Pennsylvania. He also published an abridgement of the Criminal Laws of the United States.

After his retirement, his days passed without history. He loved to dwell on his memories, for example, his interesting friendship with Charles Dickens, when the latter had visited the United States in 1842. Lewis had met Dickens on a packet boat at Harrisburg and thereafter continued to correspond with him. As late as 1868 they still exchanged letters.

His death occurred March 19, 1871. The funeral in West Philadelphia was largely attended by members of the Bench and Bar. His grave in Woodlands cemetery is marked with a simple shaft on which is carved a cross, with his name and the dates of his birth and death. His wife died January 29, 1879. Their children were: Juliet H. Lewis Campbell, a well known poetess, born August 5, 1823, died December 26, 1898; Elizabeth, who died in infancy; Ellis, born March 9, 1830, died before attaining his majority; James, born June 2, 1832, Major U.S.M.C.; Ann, born March 19, 1835, died March 8, 1893, married Capt. James Wiley; and Josephine.

25Report of the Trial and Conviction of John Earls for the Murder of his wife, Catherine Earls . . . Together with the confession of the Prisoner, reported and Prepared for publication by Wm. F. Packer and A. Cummings, Jr., Williamsport: Printed by the Publishers, 1836. Before I located a copy of this book I had laboriously read all the contemporary newspaper accounts. I now own one copy inscribed by Packer to Hon. E. B. Hubley, and another inscribed by Judge Lewis to William Rawle. Judge Charles Scott Williams, Thomas Wood, Jr., and Mrs. Martha Lego also have copies.

26Now and Then, Vol. VII, pp. 182-188 (1944)

27Article by David Paul Brown, in The Forum, Vol. II, p. 120.

28Judge Lewis had left the Society of Friends and was at this time a vestryman of the Episcopal church at Williamsport.

[Contents] [Last-Part 2] [Next-Part 4]